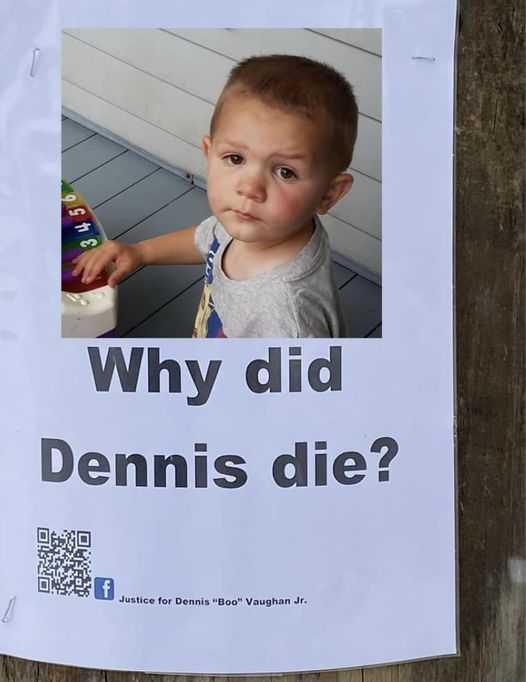

At 15, Danielle Vaughan was left in the care of her mother’s friend, who was then a 50 year old man. They became romantically involved, Danielle got pregnant, and Vaughan was a mother by the time she was 17. They married and eventually had four children. Their youngest was named Dennis. Dennis Vaughan Jr. was born in 2014, the fourth of Danielle Vaughan children.

Vaughan, now 33, has led a life marred by abuse. She remembered her mother, Sherry Connor, as erratic and prone to violent outbursts.

Danielle’s husband grew controlling and violent. Both of them started using drugs. Dennis Sr. has been repeatedly arrested for drugs. In 2016, police raided the family’s Laconia home, arresting Dennis Sr. — and Vaughan lost custody of her four children.

“That was the beginning of a horrible four years,” she said, but she was willing to move mountains to get her children back.

She kicked heroin. She went to her appointments. She found stable housing, away from Dennis Sr. She worked to piece together a life and prove she could care for her children.

In the summer of 2017, a court granted custody of the four children to Vaughan’s mother, Sherry. Vaughan had reservations about the arrangement, after the way she had grown up.

“I knew my mom had that mean bone in her body,” she said. But she wanted to believe she would love and care for her grandchildren.

Before long, Vaughan said, she started noticing the children had bruises on their wrists or their ears. One of the children was hospitalized with a concussion. Connor would always have an explanation, Vaughan said.

Then during one visit, Vaughan noticed finger-shaped bruises around her children’s chins. “I knew those bruises. I knew what they were from.”

Vaughan said her mother used to grab her by the chin, almost lifting her off the floor as she yelled, “Now you look at me.”

All the children were too skinny, Vaughan said. On a visit to Connor’s home for Christmas in 2018, she discovered their deplorable living conditions.

Connor’s home in Laconia was vile, Vaughan said, with human and dog feces on the floor. She kept the refrigerator and cabinets locked, so the children — 4-year-old Dennis and the three older children — couldn’t get food or drinks themselves. When they got too thirsty, Vaughan said, they drank out of the toilet — and were punished for it. They used a bucket to go to the bathroom.

After that visit, Vaughan figures she called DCYF every day.

But the division screened out her reports, or the cases were closed as “unfounded,” she said, meaning an investigation did not turn up abuse or neglect.

One day, Vaughan got a voicemail from her mother, who seemed to have dialed by mistake. Vaughan could hear a hand smacking flesh, her third-oldest child screaming, and her mother screaming back. “I hate you, you dirty dog,” she screamed, cursing at the 8-year-old, Vaughan remembered. “I can’t wait for someone to take you away.”

Vaughan made another report, she said.

In July 2019, Vaughan said, her mother duct-taped that same child to a chair and left him overnight in an Epsom campground. Other people in the campground called police. DCYF petitioned a court to remove the child from Connor on an emergency basis, and returned him to Vaughan.

Vaughan said she is still not clear about why the division removed only one of her children from Connor’s care in the summer of 2019 — but did not move to get her other three children, including Dennis Jr., out of Connor’s home.

By this time, Vaughan said she was calling for help multiple times a day. She called the Office of the Child Advocate, an ombudsman’s office, police, every authority she could think of. She was frantic.

“I was begging to put them anywhere else but her house,” Vaughan said.

On Christmas Eve 2019, Vaughan went into work early for her cleaning job at Elliot Hospital.

She was there less than an hour that Tuesday morning when a state police sergeant asked to talk to her. She felt a knot in her stomach as they walked into an empty room.

“He looks at me and says, ‘Dennis is dead.’”

3 years later, Danielle is still trying to get answers about how exactly her son died. In May 2020, an autopsy performed by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner said Dennis died of blunt force trauma to the head and neck, and ruled the death a homicide.

No one has been charged, Associate Attorney General Jeffery A. Strelzin said the investigation is still open.

Vaughan is trying to understand how the child welfare system failed her family so utterly.

#TrueCrime

Vaughan, now 33, has led a life marred by abuse. She remembered her mother, Sherry Connor, as erratic and prone to violent outbursts.

Danielle’s husband grew controlling and violent. Both of them started using drugs. Dennis Sr. has been repeatedly arrested for drugs. In 2016, police raided the family’s Laconia home, arresting Dennis Sr. — and Vaughan lost custody of her four children.

“That was the beginning of a horrible four years,” she said, but she was willing to move mountains to get her children back.

She kicked heroin. She went to her appointments. She found stable housing, away from Dennis Sr. She worked to piece together a life and prove she could care for her children.

In the summer of 2017, a court granted custody of the four children to Vaughan’s mother, Sherry. Vaughan had reservations about the arrangement, after the way she had grown up.

“I knew my mom had that mean bone in her body,” she said. But she wanted to believe she would love and care for her grandchildren.

Before long, Vaughan said, she started noticing the children had bruises on their wrists or their ears. One of the children was hospitalized with a concussion. Connor would always have an explanation, Vaughan said.

Then during one visit, Vaughan noticed finger-shaped bruises around her children’s chins. “I knew those bruises. I knew what they were from.”

Vaughan said her mother used to grab her by the chin, almost lifting her off the floor as she yelled, “Now you look at me.”

All the children were too skinny, Vaughan said. On a visit to Connor’s home for Christmas in 2018, she discovered their deplorable living conditions.

Connor’s home in Laconia was vile, Vaughan said, with human and dog feces on the floor. She kept the refrigerator and cabinets locked, so the children — 4-year-old Dennis and the three older children — couldn’t get food or drinks themselves. When they got too thirsty, Vaughan said, they drank out of the toilet — and were punished for it. They used a bucket to go to the bathroom.

After that visit, Vaughan figures she called DCYF every day.

But the division screened out her reports, or the cases were closed as “unfounded,” she said, meaning an investigation did not turn up abuse or neglect.

One day, Vaughan got a voicemail from her mother, who seemed to have dialed by mistake. Vaughan could hear a hand smacking flesh, her third-oldest child screaming, and her mother screaming back. “I hate you, you dirty dog,” she screamed, cursing at the 8-year-old, Vaughan remembered. “I can’t wait for someone to take you away.”

Vaughan made another report, she said.

In July 2019, Vaughan said, her mother duct-taped that same child to a chair and left him overnight in an Epsom campground. Other people in the campground called police. DCYF petitioned a court to remove the child from Connor on an emergency basis, and returned him to Vaughan.

Vaughan said she is still not clear about why the division removed only one of her children from Connor’s care in the summer of 2019 — but did not move to get her other three children, including Dennis Jr., out of Connor’s home.

By this time, Vaughan said she was calling for help multiple times a day. She called the Office of the Child Advocate, an ombudsman’s office, police, every authority she could think of. She was frantic.

“I was begging to put them anywhere else but her house,” Vaughan said.

On Christmas Eve 2019, Vaughan went into work early for her cleaning job at Elliot Hospital.

She was there less than an hour that Tuesday morning when a state police sergeant asked to talk to her. She felt a knot in her stomach as they walked into an empty room.

“He looks at me and says, ‘Dennis is dead.’”

3 years later, Danielle is still trying to get answers about how exactly her son died. In May 2020, an autopsy performed by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner said Dennis died of blunt force trauma to the head and neck, and ruled the death a homicide.

No one has been charged, Associate Attorney General Jeffery A. Strelzin said the investigation is still open.

Vaughan is trying to understand how the child welfare system failed her family so utterly.

#TrueCrime

At 15, Danielle Vaughan was left in the care of her mother’s friend, who was then a 50 year old man. They became romantically involved, Danielle got pregnant, and Vaughan was a mother by the time she was 17. They married and eventually had four children. Their youngest was named Dennis. Dennis Vaughan Jr. was born in 2014, the fourth of Danielle Vaughan children.

Vaughan, now 33, has led a life marred by abuse. She remembered her mother, Sherry Connor, as erratic and prone to violent outbursts.

Danielle’s husband grew controlling and violent. Both of them started using drugs. Dennis Sr. has been repeatedly arrested for drugs. In 2016, police raided the family’s Laconia home, arresting Dennis Sr. — and Vaughan lost custody of her four children.

“That was the beginning of a horrible four years,” she said, but she was willing to move mountains to get her children back.

She kicked heroin. She went to her appointments. She found stable housing, away from Dennis Sr. She worked to piece together a life and prove she could care for her children.

In the summer of 2017, a court granted custody of the four children to Vaughan’s mother, Sherry. Vaughan had reservations about the arrangement, after the way she had grown up.

“I knew my mom had that mean bone in her body,” she said. But she wanted to believe she would love and care for her grandchildren.

Before long, Vaughan said, she started noticing the children had bruises on their wrists or their ears. One of the children was hospitalized with a concussion. Connor would always have an explanation, Vaughan said.

Then during one visit, Vaughan noticed finger-shaped bruises around her children’s chins. “I knew those bruises. I knew what they were from.”

Vaughan said her mother used to grab her by the chin, almost lifting her off the floor as she yelled, “Now you look at me.”

All the children were too skinny, Vaughan said. On a visit to Connor’s home for Christmas in 2018, she discovered their deplorable living conditions.

Connor’s home in Laconia was vile, Vaughan said, with human and dog feces on the floor. She kept the refrigerator and cabinets locked, so the children — 4-year-old Dennis and the three older children — couldn’t get food or drinks themselves. When they got too thirsty, Vaughan said, they drank out of the toilet — and were punished for it. They used a bucket to go to the bathroom.

After that visit, Vaughan figures she called DCYF every day.

But the division screened out her reports, or the cases were closed as “unfounded,” she said, meaning an investigation did not turn up abuse or neglect.

One day, Vaughan got a voicemail from her mother, who seemed to have dialed by mistake. Vaughan could hear a hand smacking flesh, her third-oldest child screaming, and her mother screaming back. “I hate you, you dirty dog,” she screamed, cursing at the 8-year-old, Vaughan remembered. “I can’t wait for someone to take you away.”

Vaughan made another report, she said.

In July 2019, Vaughan said, her mother duct-taped that same child to a chair and left him overnight in an Epsom campground. Other people in the campground called police. DCYF petitioned a court to remove the child from Connor on an emergency basis, and returned him to Vaughan.

Vaughan said she is still not clear about why the division removed only one of her children from Connor’s care in the summer of 2019 — but did not move to get her other three children, including Dennis Jr., out of Connor’s home.

By this time, Vaughan said she was calling for help multiple times a day. She called the Office of the Child Advocate, an ombudsman’s office, police, every authority she could think of. She was frantic.

“I was begging to put them anywhere else but her house,” Vaughan said.

On Christmas Eve 2019, Vaughan went into work early for her cleaning job at Elliot Hospital.

She was there less than an hour that Tuesday morning when a state police sergeant asked to talk to her. She felt a knot in her stomach as they walked into an empty room.

“He looks at me and says, ‘Dennis is dead.’”

3 years later, Danielle is still trying to get answers about how exactly her son died. In May 2020, an autopsy performed by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner said Dennis died of blunt force trauma to the head and neck, and ruled the death a homicide.

No one has been charged, Associate Attorney General Jeffery A. Strelzin said the investigation is still open.

Vaughan is trying to understand how the child welfare system failed her family so utterly.

#TrueCrime

0 التعليقات

0 المشاركات

14231 مشاهدة