Post Your Interesting Facts.

-

Public Group

-

90 Posts

-

27 Photos

-

0 Videos

-

History and Facts

Recent Updates

-

The world’s largest waterfall is underwater.

When we think of the world’s mightiest waterfalls, we normally picture them cascading majestically over cliffs to a turbulent plunge pool far below. But the world’s largest waterfall is actually located in the ocean. Known as the Denmark Strait cataract, it flows beneath the Denmark Strait, which separates Iceland and Greenland. At the bottom of that strait, a series of cataracts — beginning some 2,000 feet beneath the surface — plunge to a depth of 10,000 feet, a drop of nearly 2 miles. This underwater waterfall exists due to density differences between the two water masses on either side of the Denmark Strait. When the southward-flowing cold water from the Nordic Seas meets the warmer water from the Irminger Sea, the cold, dense water quickly sinks below the warmer, less dense water, and plunges over a huge drop in the ocean floor. The resulting downward flow is estimated to well exceed 123 million cubic feet per second. By comparison, the discharge of the Amazon River into the Atlantic Ocean is just 7.74 million cubic feet per second.The world’s largest waterfall is underwater. When we think of the world’s mightiest waterfalls, we normally picture them cascading majestically over cliffs to a turbulent plunge pool far below. But the world’s largest waterfall is actually located in the ocean. Known as the Denmark Strait cataract, it flows beneath the Denmark Strait, which separates Iceland and Greenland. At the bottom of that strait, a series of cataracts — beginning some 2,000 feet beneath the surface — plunge to a depth of 10,000 feet, a drop of nearly 2 miles. This underwater waterfall exists due to density differences between the two water masses on either side of the Denmark Strait. When the southward-flowing cold water from the Nordic Seas meets the warmer water from the Irminger Sea, the cold, dense water quickly sinks below the warmer, less dense water, and plunges over a huge drop in the ocean floor. The resulting downward flow is estimated to well exceed 123 million cubic feet per second. By comparison, the discharge of the Amazon River into the Atlantic Ocean is just 7.74 million cubic feet per second.0 Comments 0 Shares 555 ViewsPlease log in to like, share and comment! -

What was ketchup originally made from?

Ketchup was originally made out of fish.

If you asked for ketchup thousands of years ago in Asia, you might have been handed something that looks more like today’s soy sauce. Texts as old as 300 BCE show that southern Chinese cooks were mixing together salty, fermented pastes made from fish entrails, meat byproducts, and soybeans. These easily shipped and stored concoctions — known in different dialects as “ge-thcup,” “koe-cheup,” “kêtsiap,” or “kicap” — were shared along Southeast Asian trade routes. By the early 18th century, they had become popular with British traders. Yet the recipe was tricky to recreate back in England because the country lacked soybeans. Instead, countless ketchup varieties were made by boiling down other ingredients, sometimes including anchovies or oysters, or marinating them in large quantities of salt. (Jane Austen was said to be partial to mushroom ketchup.) One crop that the English avoided in their ketchup experiments was tomatoes, which for centuries were thought to be poisonous.

Across the Atlantic, Philadelphia scientist James Mease created the first tomato-based ketchup recipe in 1812. More than half a century later, Henry J. Heinz founded his food company in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania. The first commercial tomato ketchups — including Heinz’s 1876 product — relied on chemicals to preserve their freshness and color, including formalin and coal tar. But around 1904, chief Heinz food scientist G.F. Mason devised an all-natural blend that included tomatoes, distilled vinegar, brown sugar, salt, and spices. With the signature formula now established, the brand was able to meet the growing U.S. demand for hot dogs, french fries, and hamburgers.

There’s a museum in Wisconsin entirely devoted to mustard.

At this Midwestern attraction, the showpiece is the Great Wall of Mustard, an assortment of more than 5,600 bottles and jars. Exhibits on the wall have been sourced from every U.S. state as well as 70 countries. The museum’s founder and curator is Barry Levenson, who began collecting mustard in 1986. The following year, while working for the Wisconsin Department of Justice, Levenson successfully argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court — with a jar of hotel mustard in his pocket. In the early ’90s, he left law to open the original iteration of his museum, which is now in Middleton. Tickets to the National Mustard Museum are always free, and include entry to the Mustardpiece Theatre.What was ketchup originally made from? Ketchup was originally made out of fish. If you asked for ketchup thousands of years ago in Asia, you might have been handed something that looks more like today’s soy sauce. Texts as old as 300 BCE show that southern Chinese cooks were mixing together salty, fermented pastes made from fish entrails, meat byproducts, and soybeans. These easily shipped and stored concoctions — known in different dialects as “ge-thcup,” “koe-cheup,” “kêtsiap,” or “kicap” — were shared along Southeast Asian trade routes. By the early 18th century, they had become popular with British traders. Yet the recipe was tricky to recreate back in England because the country lacked soybeans. Instead, countless ketchup varieties were made by boiling down other ingredients, sometimes including anchovies or oysters, or marinating them in large quantities of salt. (Jane Austen was said to be partial to mushroom ketchup.) One crop that the English avoided in their ketchup experiments was tomatoes, which for centuries were thought to be poisonous. Across the Atlantic, Philadelphia scientist James Mease created the first tomato-based ketchup recipe in 1812. More than half a century later, Henry J. Heinz founded his food company in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania. The first commercial tomato ketchups — including Heinz’s 1876 product — relied on chemicals to preserve their freshness and color, including formalin and coal tar. But around 1904, chief Heinz food scientist G.F. Mason devised an all-natural blend that included tomatoes, distilled vinegar, brown sugar, salt, and spices. With the signature formula now established, the brand was able to meet the growing U.S. demand for hot dogs, french fries, and hamburgers. There’s a museum in Wisconsin entirely devoted to mustard. At this Midwestern attraction, the showpiece is the Great Wall of Mustard, an assortment of more than 5,600 bottles and jars. Exhibits on the wall have been sourced from every U.S. state as well as 70 countries. The museum’s founder and curator is Barry Levenson, who began collecting mustard in 1986. The following year, while working for the Wisconsin Department of Justice, Levenson successfully argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court — with a jar of hotel mustard in his pocket. In the early ’90s, he left law to open the original iteration of his museum, which is now in Middleton. Tickets to the National Mustard Museum are always free, and include entry to the Mustardpiece Theatre.0 Comments 0 Shares 569 Views1

-

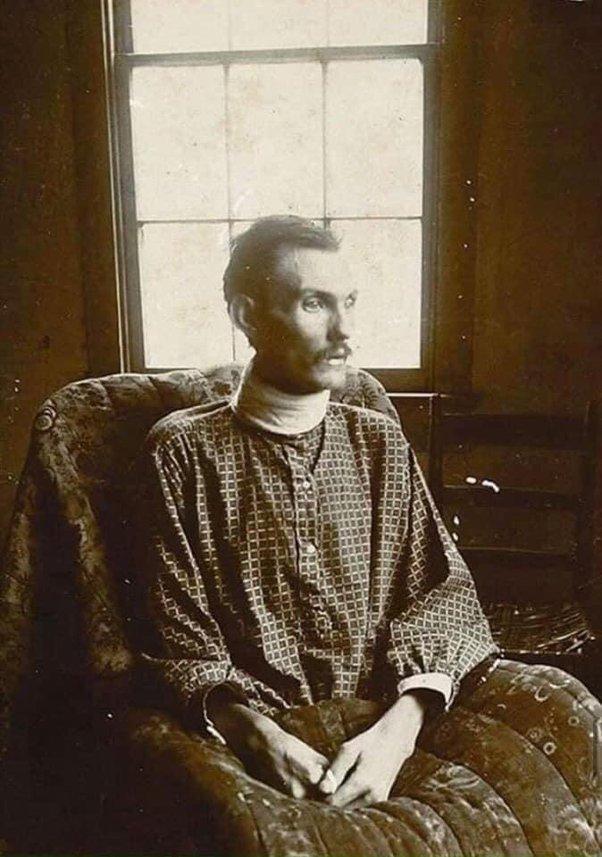

Doc Holiday, last known photo 1887

His hard living had caught up to him, forcing him to seek treatment for his tuberculosis at a sanitarium in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. He died in his bed at only 36 years old.

Last photo of Doc Holliday at the Hotel Glenwood, Glenwood Springs Colorado.

John Henry "Doc" Holliday (August 14, 1851 – November 8, 1887) was an American gambler, gunfighter, and dentist. A close friend and associate of lawman Wyatt Earp, Holliday is best known for his role in the events leading up to and following the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. He developed a reputation as having killed more than a dozen men in various altercations, but modern researchers have concluded that, contrary to popular myth-making, Holliday killed only one or two men. Holliday's colorful life and character have been depicted in many books and portrayed by well-known actors in numerous movies and television series.

In 1887, prematurely gray and badly ailing, Holliday made his way to the Hotel Glenwood, near the hot springs of Glenwood Springs, Colorado. He hoped to take advantage of the reputed curative power of the waters, but the sulfurous fumes from the spring may have done his lungs more harm than good As he lay dying, Holliday is reported to have asked the nurse attending him for a shot of whiskey. When she told him no, he looked at his bootless feet, amused. The nurses said that his last words were, "This is funny."[He always figured he would be killed someday with his boots on..Holliday died at 10am on November 8, 1887. He was 36.Wyatt Earp did not learn of Holliday's death until two months afterward.

Holliday is buried in Linwood Cemetery overlooking Glenwood Springs. The exact location of his grave is uncertain.Doc Holiday, last known photo 1887 His hard living had caught up to him, forcing him to seek treatment for his tuberculosis at a sanitarium in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. He died in his bed at only 36 years old. Last photo of Doc Holliday at the Hotel Glenwood, Glenwood Springs Colorado. John Henry "Doc" Holliday (August 14, 1851 – November 8, 1887) was an American gambler, gunfighter, and dentist. A close friend and associate of lawman Wyatt Earp, Holliday is best known for his role in the events leading up to and following the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. He developed a reputation as having killed more than a dozen men in various altercations, but modern researchers have concluded that, contrary to popular myth-making, Holliday killed only one or two men. Holliday's colorful life and character have been depicted in many books and portrayed by well-known actors in numerous movies and television series. In 1887, prematurely gray and badly ailing, Holliday made his way to the Hotel Glenwood, near the hot springs of Glenwood Springs, Colorado. He hoped to take advantage of the reputed curative power of the waters, but the sulfurous fumes from the spring may have done his lungs more harm than good As he lay dying, Holliday is reported to have asked the nurse attending him for a shot of whiskey. When she told him no, he looked at his bootless feet, amused. The nurses said that his last words were, "This is funny."[He always figured he would be killed someday with his boots on..Holliday died at 10am on November 8, 1887. He was 36.Wyatt Earp did not learn of Holliday's death until two months afterward. Holliday is buried in Linwood Cemetery overlooking Glenwood Springs. The exact location of his grave is uncertain.0 Comments 0 Shares 723 Views1

-

Estimated population of pet cats in the United Kingdom

11,000,000Estimated population of pet cats in the United Kingdom 11,000,0000 Comments 0 Shares 715 Views1

-

Halloween comes from an ancient pagan holiday.

Halloween has its roots in an ancient Celtic holiday called Samhain, traditionally celebrated in Ireland and Scotland on the night of October 31 each year. It was believed that on that night, the separation between the living world and the world of the dead broke down, allowing for interaction with the Celtic “Otherworld,” the realm of the spirits. Traditional Samhain celebrations centered around fire: The hearth was lit while the harvest was gathered, and it was left to burn out on its own. If the hearth was put out by hand, it was thought to anger the gods. Afterward, a bonfire was held to honor the dead, and people would take flame from the fire to relight the hearth at home. Celebrants would also dress up in costumes and disguises during Samhain so that evil spirits returning to Earth would not be able to recognize them. Hollowed-out root vegetables with candles inside, a precursor to jack-o’-lanterns, were used in part to scare off evil spirits, as well as to guide the way home after the Samhain celebration.Halloween comes from an ancient pagan holiday. Halloween has its roots in an ancient Celtic holiday called Samhain, traditionally celebrated in Ireland and Scotland on the night of October 31 each year. It was believed that on that night, the separation between the living world and the world of the dead broke down, allowing for interaction with the Celtic “Otherworld,” the realm of the spirits. Traditional Samhain celebrations centered around fire: The hearth was lit while the harvest was gathered, and it was left to burn out on its own. If the hearth was put out by hand, it was thought to anger the gods. Afterward, a bonfire was held to honor the dead, and people would take flame from the fire to relight the hearth at home. Celebrants would also dress up in costumes and disguises during Samhain so that evil spirits returning to Earth would not be able to recognize them. Hollowed-out root vegetables with candles inside, a precursor to jack-o’-lanterns, were used in part to scare off evil spirits, as well as to guide the way home after the Samhain celebration.0 Comments 0 Shares 755 Views -

Birthdays Weren't Always Celebrated Because Few People Even Knew Their Birthday Date.Birthdays are often a big deal in the modern world, marking milestones such as being old enough to drive or vote, or acknowledging the start of a new decade of life. But for most of human history, a birthday was just another day, and many people didn’t even know when theirs was. Ancient societies sometimes recorded births within noble or...0 Comments 0 Shares 2K Views

-

Dairy Queen doesn’t sell ice cream.

Dairy Queen makes a lot of popular frozen treats — Blizzards, sundaes, and cones, to name a few — but none of them are technically ice cream. The company’s soft serve products, though delicious, don’t meet the Food and Drug Administration guideline mandating that “ice cream contains not less than 10% milk fat.”

Because Dairy Queen’s products are made with only 5% milk fat, they’re required to be called something else. That’s why you won’t actually see the words “ice cream” at your local DQ or on the website, which is careful to use specific wording.

Soft serve and similar confections made with lower milk fat used to be classified as “ice milk” by the FDA, but new regulations in 1995 resulted in three other categories instead: reduced-fat, light, and low-fat ice cream. Dairy Queen products fall under the banner of “reduced-fat ice cream,” which is legally distinct from “ice cream” proper — and isn’t the catchiest term when trying to sell frozen desserts. Frozen yogurt, meanwhile, is made of yogurt rather than cream and hasn’t been sold at Dairy Queen since the chain discontinued the frozen yogurt-based Breeze in 2000.Dairy Queen doesn’t sell ice cream. Dairy Queen makes a lot of popular frozen treats — Blizzards, sundaes, and cones, to name a few — but none of them are technically ice cream. The company’s soft serve products, though delicious, don’t meet the Food and Drug Administration guideline mandating that “ice cream contains not less than 10% milk fat.” Because Dairy Queen’s products are made with only 5% milk fat, they’re required to be called something else. That’s why you won’t actually see the words “ice cream” at your local DQ or on the website, which is careful to use specific wording. Soft serve and similar confections made with lower milk fat used to be classified as “ice milk” by the FDA, but new regulations in 1995 resulted in three other categories instead: reduced-fat, light, and low-fat ice cream. Dairy Queen products fall under the banner of “reduced-fat ice cream,” which is legally distinct from “ice cream” proper — and isn’t the catchiest term when trying to sell frozen desserts. Frozen yogurt, meanwhile, is made of yogurt rather than cream and hasn’t been sold at Dairy Queen since the chain discontinued the frozen yogurt-based Breeze in 2000.0 Comments 0 Shares 819 Views1

-

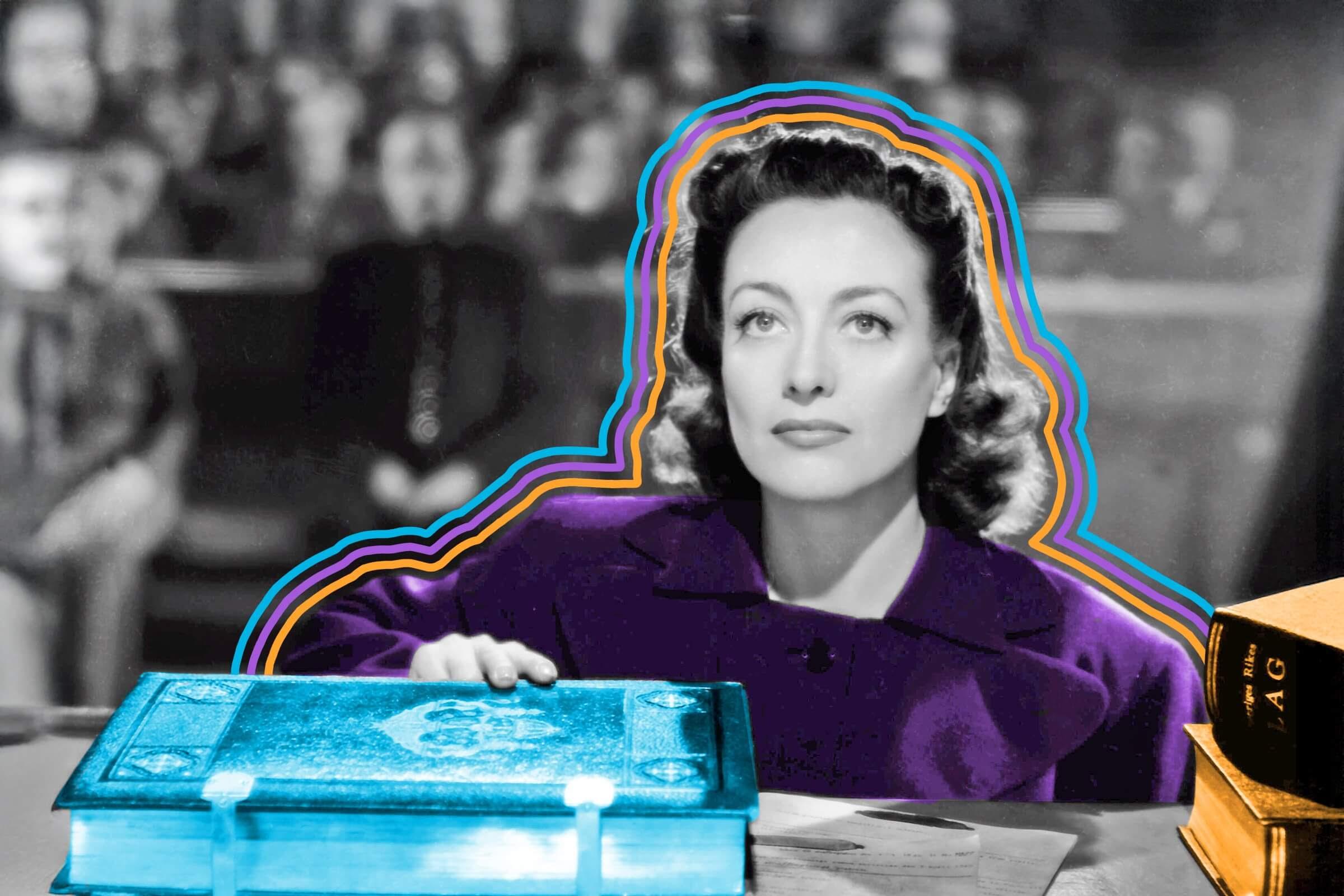

Joan Crawford’s stage name came from a public contest.

Like many classic Hollywood stars, Joan Crawford was known by a stage name rather than her real name. Born Lucille Fay LeSueur, the future Oscar winner made her silver-screen debut in 1925’s Lady of the Night under her birth name. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which had signed her to a $75-a-week contract, saw potential in the starlet but feared her name would be a hindrance; Pete Smith, the head of publicity at MGM, thought her surname sounded too much like the word “sewer.”

So the upper brass at MGM landed on a novel solution: a contest run in the fan magazine Movie Weekly, which offered between $50 and $500 for coming up with a new name for “a beautiful young screen actress.” The perfect name, according to MGM, “must be moderately short and euphonious. It must not imitate the name of some already established artiste. It must be easy to spell, pronounce, and remember. It must be impressive and suitable to the bearer’s type.”

The winner, as fate would have it, wasn’t Joan Crawford; it was Joan Arden, which was already the name of an extra who threatened to sue MGM. And so the second-place winner was chosen instead, not that the new Joan Crawford was happy about it — she initially hated the name before making the most of it.

Crawford accepted her Oscar from bed.

After a string of hits in the late 1920s and early ’30s, Crawford’s luck so reversed itself that she was deemed “box-office poison” in TIME magazine by the end of the decade. Her comeback wasn’t fully solidified until she took the title role in 1945’s Mildred Pierce, which resulted in her sole Academy Award — not that she was expecting to win. Believing Ingrid Bergman would take home the Oscar for The Bells of St. Mary’s, Crawford was disinclined to attend any ceremony where she wouldn’t be victorious and opted to feign illness. Upon learning she’d won, however, she put on her makeup, invited members of the press to her bedroom, and accepted the statuette from the comfort of her own bed.Joan Crawford’s stage name came from a public contest. Like many classic Hollywood stars, Joan Crawford was known by a stage name rather than her real name. Born Lucille Fay LeSueur, the future Oscar winner made her silver-screen debut in 1925’s Lady of the Night under her birth name. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which had signed her to a $75-a-week contract, saw potential in the starlet but feared her name would be a hindrance; Pete Smith, the head of publicity at MGM, thought her surname sounded too much like the word “sewer.” So the upper brass at MGM landed on a novel solution: a contest run in the fan magazine Movie Weekly, which offered between $50 and $500 for coming up with a new name for “a beautiful young screen actress.” The perfect name, according to MGM, “must be moderately short and euphonious. It must not imitate the name of some already established artiste. It must be easy to spell, pronounce, and remember. It must be impressive and suitable to the bearer’s type.” The winner, as fate would have it, wasn’t Joan Crawford; it was Joan Arden, which was already the name of an extra who threatened to sue MGM. And so the second-place winner was chosen instead, not that the new Joan Crawford was happy about it — she initially hated the name before making the most of it. Crawford accepted her Oscar from bed. After a string of hits in the late 1920s and early ’30s, Crawford’s luck so reversed itself that she was deemed “box-office poison” in TIME magazine by the end of the decade. Her comeback wasn’t fully solidified until she took the title role in 1945’s Mildred Pierce, which resulted in her sole Academy Award — not that she was expecting to win. Believing Ingrid Bergman would take home the Oscar for The Bells of St. Mary’s, Crawford was disinclined to attend any ceremony where she wouldn’t be victorious and opted to feign illness. Upon learning she’d won, however, she put on her makeup, invited members of the press to her bedroom, and accepted the statuette from the comfort of her own bed.0 Comments 0 Shares 896 Views -

-

More Stories

Join the group to join the chatbox