Wild West Facts.

- Public Group

- 56 Posts

- 35 Photos

- 0 Videos

- History and Facts

Recent Updates

- The $6 Million ShotThe Real Story Behind the Gun that Killed Billy the Kid They say history is written by the victors, but sometimes it’s pawned, litigated, forgotten—and eventually sold for over $6 million at auction. That’s the real story behind the most infamous pistol in Western lore: the one Pat Garrett used to kill Billy the Kid. It started not in a saloon or a...0 Comments 0 Shares 1144 ViewsPlease log in to like, share and comment!

- April 16th, 1881

Western gunslinger, Bat Masterson, fights in last shootout.

On the streets of Dodge City, famous western lawman and gunfighter Bat Masterson fights what is the last documented gun battle of his life.

Bartholomew “Bat” Masterson had made a living with his gun from a young age. In his early 20s, Masterson worked as a buffalo hunter, operating out of the wild Kansas cattle town of Dodge City. For several years, he also found employment as an army scout in the Plains Indian Wars. Masterson had his first shootout in 1876 in the town of Sweetwater (later Mobeetie), Texas. When an argument with a soldier over the affections of a dance hall girl named Molly Brennan heated up, Masterson and his opponent resorted to their pistols. When the shooting stopped, both Brennan and the soldier were dead, and Masterson was badly wounded.

Found to have been acting in self-defense, Masterson avoided prison. Once he had recovered from his wounds, he apparently decided to abandon his rough ways and become an officer of the law. For the next five years, Masterson alternated between work as Dodge City sheriff and running saloons and gambling houses, gaining a reputation as a tough and reliable lawman. However, Masterson’s critics claimed that he spent too much as sheriff, and he lost a bid for reelection in 1879.

For several years, Masterson drifted around the West. Early in 1881, news that his younger brother, Jim, was in trouble back in Dodge City reached Masterson in Tombstone, Arizona. Jim’s dispute with a business partner and an employee, A.J. Peacock and Al Updegraff respectively, had led to an exchange of gunfire. Though no one had yet been hurt, Jim feared for his life. Masterson immediately took a train to Dodge City.

When his train pulled into Dodge City on this morning in 1881, Masterson wasted no time. He quickly spotted Peacock and Updegraff and aggressively shouldered his way through the crowded street to confront them. “I have come over a thousand miles to settle this,” Masterson reportedly shouted. “I know you are heeled [armed]-now fight!” All three men immediately drew their guns. Masterson took cover behind the railway bed, while Peacock and Updegraff darted around the corner of the city jail. Several other men joined in the gunplay. One bullet meant for Masterson ricocheted and wounded a bystander. Updegraff took a bullet in his right lung.

The mayor and sheriff arrived with shotguns to stop the battle when a brief lull settled over the scene. Updegraff and the wounded bystander were taken to the doctor and both eventually recovered. In fact, no one was mortally injured in the melee, and since the shootout had been fought fairly by the Dodge City standards of the day, no serious charges were imposed against Masterson. He paid an $8 fine and took the train out of Dodge City that evening.

Masterson never again fought a gun battle in his life, but the story of the Dodge City shootout and his other exploits ensured Masterson’s lasting fame as an icon of the Old West. He spent the next four decades of his life working as sheriff, operating saloons, and eventually trying his hand as a newspaperman in New York City. The old gunfighter finally died of a heart attack in October 1921 at his desk in New York City.April 16th, 1881 Western gunslinger, Bat Masterson, fights in last shootout. On the streets of Dodge City, famous western lawman and gunfighter Bat Masterson fights what is the last documented gun battle of his life. Bartholomew “Bat” Masterson had made a living with his gun from a young age. In his early 20s, Masterson worked as a buffalo hunter, operating out of the wild Kansas cattle town of Dodge City. For several years, he also found employment as an army scout in the Plains Indian Wars. Masterson had his first shootout in 1876 in the town of Sweetwater (later Mobeetie), Texas. When an argument with a soldier over the affections of a dance hall girl named Molly Brennan heated up, Masterson and his opponent resorted to their pistols. When the shooting stopped, both Brennan and the soldier were dead, and Masterson was badly wounded. Found to have been acting in self-defense, Masterson avoided prison. Once he had recovered from his wounds, he apparently decided to abandon his rough ways and become an officer of the law. For the next five years, Masterson alternated between work as Dodge City sheriff and running saloons and gambling houses, gaining a reputation as a tough and reliable lawman. However, Masterson’s critics claimed that he spent too much as sheriff, and he lost a bid for reelection in 1879. For several years, Masterson drifted around the West. Early in 1881, news that his younger brother, Jim, was in trouble back in Dodge City reached Masterson in Tombstone, Arizona. Jim’s dispute with a business partner and an employee, A.J. Peacock and Al Updegraff respectively, had led to an exchange of gunfire. Though no one had yet been hurt, Jim feared for his life. Masterson immediately took a train to Dodge City. When his train pulled into Dodge City on this morning in 1881, Masterson wasted no time. He quickly spotted Peacock and Updegraff and aggressively shouldered his way through the crowded street to confront them. “I have come over a thousand miles to settle this,” Masterson reportedly shouted. “I know you are heeled [armed]-now fight!” All three men immediately drew their guns. Masterson took cover behind the railway bed, while Peacock and Updegraff darted around the corner of the city jail. Several other men joined in the gunplay. One bullet meant for Masterson ricocheted and wounded a bystander. Updegraff took a bullet in his right lung. The mayor and sheriff arrived with shotguns to stop the battle when a brief lull settled over the scene. Updegraff and the wounded bystander were taken to the doctor and both eventually recovered. In fact, no one was mortally injured in the melee, and since the shootout had been fought fairly by the Dodge City standards of the day, no serious charges were imposed against Masterson. He paid an $8 fine and took the train out of Dodge City that evening. Masterson never again fought a gun battle in his life, but the story of the Dodge City shootout and his other exploits ensured Masterson’s lasting fame as an icon of the Old West. He spent the next four decades of his life working as sheriff, operating saloons, and eventually trying his hand as a newspaperman in New York City. The old gunfighter finally died of a heart attack in October 1921 at his desk in New York City.0 Comments 0 Shares 900 Views - April 3, 1882 Jesse James is murdered.

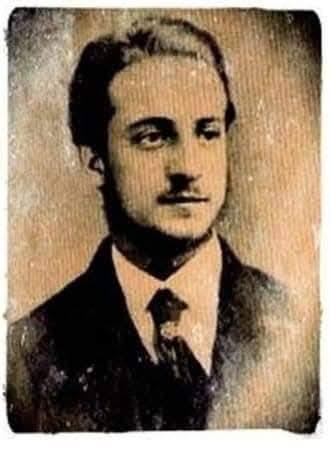

One of America’s most famous criminals, Jesse James, is shot to death by fellow gang member Bob Ford, who betrayed James for reward money. For 16 years, Jesse and his brother, Frank, committed robberies and murders throughout the Midwest. Detective magazines and pulp novels glamorized the James gang, turning them into mythical Robin Hoods who were driven to crime by unethical landowners and bankers. In reality, Jesse James was a ruthless killer who stole only for himself.

The teenage James brothers joined up with southern guerrilla leaders when the Civil War broke out. Both participated in massacres of settlers and troops affiliated with the North. After the war was over, the quiet farming life of the James brothers’ youth no longer seemed enticing, and the two turned to crime. Jesse’s first bank robbery occurred on February 13, 1866, in Liberty, Missouri.

Over the next couple of years, the James brothers became the suspects in several bank robberies throughout western Missouri. However, locals were sympathetic to ex-southern guerrillas and vouched for the brothers. Throughout the late 1860s and early 1870s, the James gang robbed only a couple of banks a year, otherwise keeping a low profile.

In 1873, the James gang got into the train robbery game. During one such robbery, the gang declined to take any money or valuables from southerners. The train robberies brought out the Pinkerton Detective Agency, employed to bring the James gang to justice. However, the Pinkerton operatives’ botched attempt to kill James left a woman and her child injured and elicited public sympathy for Jesse and Frank James.

The James gang suffered a setback in 1876 when they raided the town of Northfield, Minnesota. The Younger brothers, cousins of the James brothers, were shot and wounded during the brazen midday robbery. After running off in a different direction from Jesse and Frank, the Younger brothers were captured by a large posse and later sentenced to life in prison. Jesse and Frank, the only members of the gang to escape successfully, headed to Tennessee to hide out.

After spending a few quiet years farming, Jesse organized a new gang. Charlie and Robert Ford were on the fringe of the new gang, but they disliked Jesse intensely and decided to kill him for the reward money. On April 3, while Jesse’s mother made breakfast, the new gang met to hear Jesse’s plan for the next robbery. When Jesse turned his back to adjust a picture on the wall, Bob Ford shot him several times in the back.

His tombstone reads, “Jesse W. James, Died April 3, 1882, Aged 34 years, 6 months, 28 days, Murdered by a traitor and a coward whose name is not worthy to appear here.”April 3, 1882 Jesse James is murdered. One of America’s most famous criminals, Jesse James, is shot to death by fellow gang member Bob Ford, who betrayed James for reward money. For 16 years, Jesse and his brother, Frank, committed robberies and murders throughout the Midwest. Detective magazines and pulp novels glamorized the James gang, turning them into mythical Robin Hoods who were driven to crime by unethical landowners and bankers. In reality, Jesse James was a ruthless killer who stole only for himself. The teenage James brothers joined up with southern guerrilla leaders when the Civil War broke out. Both participated in massacres of settlers and troops affiliated with the North. After the war was over, the quiet farming life of the James brothers’ youth no longer seemed enticing, and the two turned to crime. Jesse’s first bank robbery occurred on February 13, 1866, in Liberty, Missouri. Over the next couple of years, the James brothers became the suspects in several bank robberies throughout western Missouri. However, locals were sympathetic to ex-southern guerrillas and vouched for the brothers. Throughout the late 1860s and early 1870s, the James gang robbed only a couple of banks a year, otherwise keeping a low profile. In 1873, the James gang got into the train robbery game. During one such robbery, the gang declined to take any money or valuables from southerners. The train robberies brought out the Pinkerton Detective Agency, employed to bring the James gang to justice. However, the Pinkerton operatives’ botched attempt to kill James left a woman and her child injured and elicited public sympathy for Jesse and Frank James. The James gang suffered a setback in 1876 when they raided the town of Northfield, Minnesota. The Younger brothers, cousins of the James brothers, were shot and wounded during the brazen midday robbery. After running off in a different direction from Jesse and Frank, the Younger brothers were captured by a large posse and later sentenced to life in prison. Jesse and Frank, the only members of the gang to escape successfully, headed to Tennessee to hide out. After spending a few quiet years farming, Jesse organized a new gang. Charlie and Robert Ford were on the fringe of the new gang, but they disliked Jesse intensely and decided to kill him for the reward money. On April 3, while Jesse’s mother made breakfast, the new gang met to hear Jesse’s plan for the next robbery. When Jesse turned his back to adjust a picture on the wall, Bob Ford shot him several times in the back. His tombstone reads, “Jesse W. James, Died April 3, 1882, Aged 34 years, 6 months, 28 days, Murdered by a traitor and a coward whose name is not worthy to appear here.”0 Comments 0 Shares 907 Views1

- April 3, 1876 Wyatt Earp dropped from Wichita police force.

After a public disturbance occurred between policeman Wyatt Earp and a candidate for Wichita, Kansas county sheriff, Earp is fined $30 and relieved of his job.

Born in 1848, Wyatt was one of the five Earp brothers, some of whom became famous for their participation in the shootout at the O.K. Corral in 1881. Before moving to Tombstone in 1879, however, Wyatt had already become a controversial figure. For much of his life, he worked in law enforcement, but his own allegiance to the rule of law was conditional at best.

In 1870, residents of Lamar, Missouri, elected Wyatt town constable. He did a good job as constable, but within a year his wife died of typhoid and he began wandering about the West. Not long after, Wyatt was arrested for stealing horses in Indian Territory, and he fled to Kansas to escape prosecution.

In 1873, Wyatt joined his older brother James in Wichita, Kansas, the rowdy cattle town that was the northern terminus of the Chisholm Trail. Wyatt again pinned on a badge. At first, it appears that he worked for a private security force employed by local saloons and businesses to keep order, but Wichita Marshal Michael Meagher hired him as an official city policeman by 1875.

Wyatt soon proved to be a daunting police officer. He knew how to use his Remington pistol, and he kept his skills sharp with frequent sessions of target practice. However, Wyatt also liked the Remington because it had a strap that made it an effective club: whenever possible, he preferred to pistol-whip his opponents rather than shoot them. He was also a formidable fist fighter. His friend and fellow law officer, Bat Masterson, later recalled that, “There were few men in the West who could whip Earp in a rough-and-tumble fight.”

During the next year, Wyatt again proved his mettle as a law officer, but his political skills were less refined. In April, Wichita held an election for city marshal. An opponent named William Smith challenged Wyatt’s boss, Michael Meagher, for the office. On April 2, Smith made several disparaging remarks about Meagher, and Wyatt took offense. Wyatt confronted Smith and beat him in a fistfight.

Although Meagher won reelection, he was unable to save Wyatt’s job. On April 19, 1876, a Wichita commission decided that Wyatt’s violent behavior was unacceptable and did not rehire him as a police officer. As the town newspaper conceded, “It is but justice to Earp to say he has made an excellent officer,” but the young lawman had to learn to control his passions and play the political game.

After losing his job in Wichita, Wyatt immediately moved to Dodge City, where he found work on the police force. A few years later he joined several of his brothers in the booming mining town of Tombstone, Arizona. Unfortunately, wherever Wyatt traveled, trouble seemed to follow. In 1881, the controversial gun battle at the O.K. Corral again raised questions about Wyatt’s fidelity to the rule of law. Many claimed Wyatt helped kill Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury at the O.K. Corral not for legitimate law enforcement reasons, but because of a personal feud between the Earp brothers and the Clanton-McLaury clans. Although exonerated by a local Justice of the Peace, Wyatt was soon after involved in several other questionable murders, and he was eventually forced to flee Tombstone.

Wyatt Earp seemed unable to control his passions or play the political game, though his propensity for solving problems with bloodshed waned as he grew older. He spent the next five decades of a long and interesting life wandering around the West, dabbling in mostly unsuccessful business ventures in gold, silver, and oil. He eventually settled in Los Angeles, where he died in 1929 at the age of 80.April 3, 1876 Wyatt Earp dropped from Wichita police force. After a public disturbance occurred between policeman Wyatt Earp and a candidate for Wichita, Kansas county sheriff, Earp is fined $30 and relieved of his job. Born in 1848, Wyatt was one of the five Earp brothers, some of whom became famous for their participation in the shootout at the O.K. Corral in 1881. Before moving to Tombstone in 1879, however, Wyatt had already become a controversial figure. For much of his life, he worked in law enforcement, but his own allegiance to the rule of law was conditional at best. In 1870, residents of Lamar, Missouri, elected Wyatt town constable. He did a good job as constable, but within a year his wife died of typhoid and he began wandering about the West. Not long after, Wyatt was arrested for stealing horses in Indian Territory, and he fled to Kansas to escape prosecution. In 1873, Wyatt joined his older brother James in Wichita, Kansas, the rowdy cattle town that was the northern terminus of the Chisholm Trail. Wyatt again pinned on a badge. At first, it appears that he worked for a private security force employed by local saloons and businesses to keep order, but Wichita Marshal Michael Meagher hired him as an official city policeman by 1875. Wyatt soon proved to be a daunting police officer. He knew how to use his Remington pistol, and he kept his skills sharp with frequent sessions of target practice. However, Wyatt also liked the Remington because it had a strap that made it an effective club: whenever possible, he preferred to pistol-whip his opponents rather than shoot them. He was also a formidable fist fighter. His friend and fellow law officer, Bat Masterson, later recalled that, “There were few men in the West who could whip Earp in a rough-and-tumble fight.” During the next year, Wyatt again proved his mettle as a law officer, but his political skills were less refined. In April, Wichita held an election for city marshal. An opponent named William Smith challenged Wyatt’s boss, Michael Meagher, for the office. On April 2, Smith made several disparaging remarks about Meagher, and Wyatt took offense. Wyatt confronted Smith and beat him in a fistfight. Although Meagher won reelection, he was unable to save Wyatt’s job. On April 19, 1876, a Wichita commission decided that Wyatt’s violent behavior was unacceptable and did not rehire him as a police officer. As the town newspaper conceded, “It is but justice to Earp to say he has made an excellent officer,” but the young lawman had to learn to control his passions and play the political game. After losing his job in Wichita, Wyatt immediately moved to Dodge City, where he found work on the police force. A few years later he joined several of his brothers in the booming mining town of Tombstone, Arizona. Unfortunately, wherever Wyatt traveled, trouble seemed to follow. In 1881, the controversial gun battle at the O.K. Corral again raised questions about Wyatt’s fidelity to the rule of law. Many claimed Wyatt helped kill Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury at the O.K. Corral not for legitimate law enforcement reasons, but because of a personal feud between the Earp brothers and the Clanton-McLaury clans. Although exonerated by a local Justice of the Peace, Wyatt was soon after involved in several other questionable murders, and he was eventually forced to flee Tombstone. Wyatt Earp seemed unable to control his passions or play the political game, though his propensity for solving problems with bloodshed waned as he grew older. He spent the next five decades of a long and interesting life wandering around the West, dabbling in mostly unsuccessful business ventures in gold, silver, and oil. He eventually settled in Los Angeles, where he died in 1929 at the age of 80.0 Comments 0 Shares 922 Views1

- On February 18, 1878, John Henry Tunstall was killed approximately 100 yards off a trail in a canyon outside Lincoln. On June 13, 1878, the men involved provided testimony to Special Agent Frank Warner Angel. To historians, this has become known as the "Angel Report." The following testimony was provided by Regulator John Middleton. I feel he provided more details than others & he was the last man to see Tunstall before they were separated.

The Territory of New Mexico

County of Lincoln

Personally appeared John Middleton, who having been duly sworn according to law, deposes and saith. I have lived in Lincoln, N.M., about one year. I follow the business of herding and driving cattle.

I knew John Tunstall in his lifetime. He was murdered on or about the 18th day of February, A.D. 1878, about 10 miles from the town of San Patricio in said County.

I was in the employ of said Tunstall from the 20th day of October 1877 until the time of his death as aforesaid, caring for his cattle at his ranch on the Rio Feliz. Somewhere between the 12th and 15th day if Feby, 1878, whilst at said ranch with my fellow workers R.M. Brewer, W. Bonney, F.T. Waite, G. Gauss, Martin ("Dutch" Martin Martz), and R.A. Widenmann. J.B. Matthew's, who represented himself as a Deputy Sheriff of said Lincoln Co., with Jesse Evans, Tom Hill, Frank Baker, Frank Rivers (Long), notorious murderers, escaped prisoners and horse thieves, and John Hurley and George Hindman and Bill Wiiliams alias A.L. Roberts, since killed at the Agency in said County, came to the said ranch.

R.A. Widenmann or R.M. Brewer, seeing Matthews & posse come towards the house, went out and asked Matthews to stop, asking Matthews to come alone and make his business known. Matthews said he had an attachment against the property of Alex A. McSween and was looking for property belonging to said McSween. Brewer told him that McSween had no cattle or other property there. But that he could look through the cattle and if there was any he would help him and posse to round them up, but that he could not have Tunstall's or anybody else's cattle without an order therefor.

Matthews said that he would go back to Lincoln and get instructions from Brady, and that if he returned he would have more than one or two men with him. Matthews & posse then left Frank Baker and Bill Williams, alias A.L. Roberts aforesaid, and went to J.J. Dolan's cow camp on the Pecos.

On or about the night of the 17th day if February, 1878, John H. Tunstall, deceased, arrived at his ranch, where I and others were as aforesaid, and told us to get ready to leave next morning for the town of Lincoln as he had learnt that J.J. Dolan &Co. had raised about 40 or 45 men for said Matthews as posse and intended to kill all of us at said ranch.

On the morning of the 18th Feby, 1878, said Tunstall, Widenmann, Brewer, Bonney, and Waite and deponent left for Lincoln, Waite taking the main road, the balance taking a trail.

When about 30 miles from said ranch we scattered for the purpose of hunting some turkeys. While so hunting we heard yelling and saw a large crowd of men coming over the brow of the hill, firing as they were coming. Tunstall and I were on the side of a hill, about 700 yards from horses we were bringing from the Feliz ranch to Lincoln, belonging to Tunstall, Widenman, Bonney, Brewer and myself--the horses numbered nine. If they wanted the horses they could easily have got them without coming within 700 yards of us.

Not one of those I have named as being with Tunstall fired a shot. We endeavored to escape for our lives. I was within 30 steps of Tunstall when we heard the shooting first. I sang out to Tunstall to follow me. He was on a good horse. He appeared to be very much excited and confused. I kept singing out to him for God's sake to follow me. His last word was "What John! What John!"

With the exception of Tunstall, we all made an effort to join each other. Geo. Hindman, Jessie Evans, Tom Cochrane & Baker (Frank) were the only ones I can remember now who were of the posse that murdered Tunstall. I have been informed by Tom Green who was of that posse that Jessie Evans shot Tunstall first in the breast.

Tunstall before this had surrendered his pistol, the only weapon he had, to W. Morton, deceased. When Tunstall received the first shot in the breast, he turned, moved and fell on his face. Morton then, out of Tunstall's own pistol, fired a shot at Tunstall, the ball entering the back of his head. Morton then fired another shot out of Tunstall's pistol at Tunstall's horse and killed him. Sam Perry then proposed that they should carry Tunstall's corpse and lay it by the side of the dead horse, which was done. I saw the corpse of said Tunstall at the house of Alex A. McSween in the town of Lincoln.

John Middleton

Sworn and subscribed before me this 13 day of June 1878

John B. Wilson

Justice of the PeaceOn February 18, 1878, John Henry Tunstall was killed approximately 100 yards off a trail in a canyon outside Lincoln. On June 13, 1878, the men involved provided testimony to Special Agent Frank Warner Angel. To historians, this has become known as the "Angel Report." The following testimony was provided by Regulator John Middleton. I feel he provided more details than others & he was the last man to see Tunstall before they were separated. The Territory of New Mexico County of Lincoln Personally appeared John Middleton, who having been duly sworn according to law, deposes and saith. I have lived in Lincoln, N.M., about one year. I follow the business of herding and driving cattle. I knew John Tunstall in his lifetime. He was murdered on or about the 18th day of February, A.D. 1878, about 10 miles from the town of San Patricio in said County. I was in the employ of said Tunstall from the 20th day of October 1877 until the time of his death as aforesaid, caring for his cattle at his ranch on the Rio Feliz. Somewhere between the 12th and 15th day if Feby, 1878, whilst at said ranch with my fellow workers R.M. Brewer, W. Bonney, F.T. Waite, G. Gauss, Martin ("Dutch" Martin Martz), and R.A. Widenmann. J.B. Matthew's, who represented himself as a Deputy Sheriff of said Lincoln Co., with Jesse Evans, Tom Hill, Frank Baker, Frank Rivers (Long), notorious murderers, escaped prisoners and horse thieves, and John Hurley and George Hindman and Bill Wiiliams alias A.L. Roberts, since killed at the Agency in said County, came to the said ranch. R.A. Widenmann or R.M. Brewer, seeing Matthews & posse come towards the house, went out and asked Matthews to stop, asking Matthews to come alone and make his business known. Matthews said he had an attachment against the property of Alex A. McSween and was looking for property belonging to said McSween. Brewer told him that McSween had no cattle or other property there. But that he could look through the cattle and if there was any he would help him and posse to round them up, but that he could not have Tunstall's or anybody else's cattle without an order therefor. Matthews said that he would go back to Lincoln and get instructions from Brady, and that if he returned he would have more than one or two men with him. Matthews & posse then left Frank Baker and Bill Williams, alias A.L. Roberts aforesaid, and went to J.J. Dolan's cow camp on the Pecos. On or about the night of the 17th day if February, 1878, John H. Tunstall, deceased, arrived at his ranch, where I and others were as aforesaid, and told us to get ready to leave next morning for the town of Lincoln as he had learnt that J.J. Dolan &Co. had raised about 40 or 45 men for said Matthews as posse and intended to kill all of us at said ranch. On the morning of the 18th Feby, 1878, said Tunstall, Widenmann, Brewer, Bonney, and Waite and deponent left for Lincoln, Waite taking the main road, the balance taking a trail. When about 30 miles from said ranch we scattered for the purpose of hunting some turkeys. While so hunting we heard yelling and saw a large crowd of men coming over the brow of the hill, firing as they were coming. Tunstall and I were on the side of a hill, about 700 yards from horses we were bringing from the Feliz ranch to Lincoln, belonging to Tunstall, Widenman, Bonney, Brewer and myself--the horses numbered nine. If they wanted the horses they could easily have got them without coming within 700 yards of us. Not one of those I have named as being with Tunstall fired a shot. We endeavored to escape for our lives. I was within 30 steps of Tunstall when we heard the shooting first. I sang out to Tunstall to follow me. He was on a good horse. He appeared to be very much excited and confused. I kept singing out to him for God's sake to follow me. His last word was "What John! What John!" With the exception of Tunstall, we all made an effort to join each other. Geo. Hindman, Jessie Evans, Tom Cochrane & Baker (Frank) were the only ones I can remember now who were of the posse that murdered Tunstall. I have been informed by Tom Green who was of that posse that Jessie Evans shot Tunstall first in the breast. Tunstall before this had surrendered his pistol, the only weapon he had, to W. Morton, deceased. When Tunstall received the first shot in the breast, he turned, moved and fell on his face. Morton then, out of Tunstall's own pistol, fired a shot at Tunstall, the ball entering the back of his head. Morton then fired another shot out of Tunstall's pistol at Tunstall's horse and killed him. Sam Perry then proposed that they should carry Tunstall's corpse and lay it by the side of the dead horse, which was done. I saw the corpse of said Tunstall at the house of Alex A. McSween in the town of Lincoln. John Middleton Sworn and subscribed before me this 13 day of June 1878 John B. Wilson Justice of the Peace0 Comments 0 Shares 1092 Views1

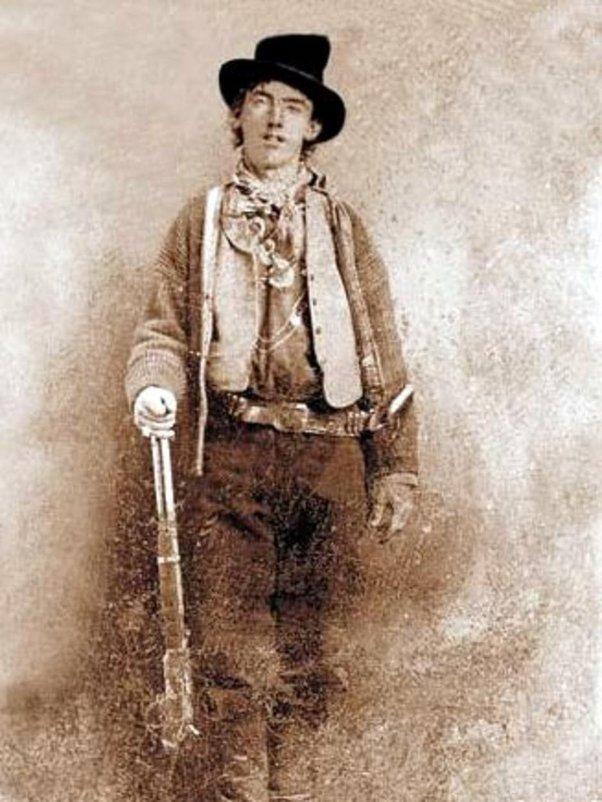

- Murder ignites Lincoln County War.

On This Day In History, February 18, 1878.

Long simmering tensions in Lincoln County, New Mexico, explode into a bloody shooting war when gunmen murder the English rancher John Tunstall.

Tunstall had established a large ranching operation in Lincoln County two years earlier in 1876, stepping into the middle of a dangerous political and economic rivalry for control of the region. Two Irish-Americans, J.J. Dolan and L.G. Murphy, operated a general store called The House, which controlled access to lucrative beef contracts with the government. The big ranchers, led by John Chisum and Alexander McSween, didn’t believe merchants should dominate the beef markets and began to challenge The House.

Tunstall, a wealthy young English emigrant, soon realized that his interests were with Chisum and McSween in this conflict, and he became a leader of the anti-House forces. He won Dolan’s and Murphy’s lasting enmity by establishing a competing general merchandise store in Lincoln. By 1877, the power struggle was threatening to become overtly violent, and Tunstall began to hire young gunmen for protection, including the soon-to-be-infamous William Bonney, better known as Billy the Kid.

Early the next year, The House used its considerable political resources to strike back at Tunstall, winning a court order demanding that Tunstall turn over some of his horses to pay an outstanding debt. When Tunstall refused to turn over the horses, the House-controlled Lincoln County sheriff dispatched a posse-with William Morton, another House supporter, at the head-to take them. Billy the Kid and several other Tunstall hands were working on the ranch when they spotted the approaching posse. Outnumbered, the men fled, but they had not gone far before they saw Tunstall gallop straight up to the posse to protest its presence on his property. As Billy and the others watched, Morton pulled his gun and shot Tunstall dead with a bullet to the head.

Although he had not worked for Tunstall long, Billy the Kid deeply resented this cold-blooded murder, and he immediately began a vendetta of violence against The House and its allies. Lincoln County became a war zone, and both sides began a spree of vicious killings. By July, The House was prevailing, having added McSween to its lists of victims. However, fighting would continue to erupt sporadically until 1884, when Chisum died of natural causes, and The House finally regained full control of Lincoln County. By that time, Billy the Kid had already been dead for three years, gunned down by Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett.

#Billy The Kid

Murder ignites Lincoln County War. On This Day In History, February 18, 1878. Long simmering tensions in Lincoln County, New Mexico, explode into a bloody shooting war when gunmen murder the English rancher John Tunstall. Tunstall had established a large ranching operation in Lincoln County two years earlier in 1876, stepping into the middle of a dangerous political and economic rivalry for control of the region. Two Irish-Americans, J.J. Dolan and L.G. Murphy, operated a general store called The House, which controlled access to lucrative beef contracts with the government. The big ranchers, led by John Chisum and Alexander McSween, didn’t believe merchants should dominate the beef markets and began to challenge The House. Tunstall, a wealthy young English emigrant, soon realized that his interests were with Chisum and McSween in this conflict, and he became a leader of the anti-House forces. He won Dolan’s and Murphy’s lasting enmity by establishing a competing general merchandise store in Lincoln. By 1877, the power struggle was threatening to become overtly violent, and Tunstall began to hire young gunmen for protection, including the soon-to-be-infamous William Bonney, better known as Billy the Kid. Early the next year, The House used its considerable political resources to strike back at Tunstall, winning a court order demanding that Tunstall turn over some of his horses to pay an outstanding debt. When Tunstall refused to turn over the horses, the House-controlled Lincoln County sheriff dispatched a posse-with William Morton, another House supporter, at the head-to take them. Billy the Kid and several other Tunstall hands were working on the ranch when they spotted the approaching posse. Outnumbered, the men fled, but they had not gone far before they saw Tunstall gallop straight up to the posse to protest its presence on his property. As Billy and the others watched, Morton pulled his gun and shot Tunstall dead with a bullet to the head. Although he had not worked for Tunstall long, Billy the Kid deeply resented this cold-blooded murder, and he immediately began a vendetta of violence against The House and its allies. Lincoln County became a war zone, and both sides began a spree of vicious killings. By July, The House was prevailing, having added McSween to its lists of victims. However, fighting would continue to erupt sporadically until 1884, when Chisum died of natural causes, and The House finally regained full control of Lincoln County. By that time, Billy the Kid had already been dead for three years, gunned down by Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett. #Billy The Kid0 Comments 0 Shares 1117 Views - Behind The Eight Ball.March 18, 1882 Morgan Earp vs. Frank Stilwell, Pete Spence and others. A one-night showing of the play Stolen Kisses is being staged at the Turnverein Hall, north of Schieffelin Hall. It has been two and a half months since Virgil Earp was shot, and, after a flurry of posses, raids, charges and counter-charges over the cow-boy killings, things are once again quiet in...0 Comments 0 Shares 2706 Views

- Who Was Dave Rudabaugh?David Rudabaugh (July 14, 1854 – February 18, 1886) was a cowboy, outlaw and gunfighter in the American Old West. Modern writers often refer to him as "Dirty Dave" because of his alleged aversion to water, though no evidence has emerged to show that he was ever referred to as such in his own lifetime. Rudabaugh was born in Fulton County,...0 Comments 0 Shares 2660 Views

- Who Was Doc Scurlock?American Old West figure, cowboy, and gunfighter Josiah Gordon "Doc" Scurlock (January 11, 1849 – July 25, 1929) was an American Old West figure, cowboy, and gunfighter. A founding member of the Regulators during the Lincoln County War in New Mexico, Scurlock rode alongside such men as Billy the Kid. He was born in Tallapoosa County, Alabama, January 11, 1849,...0 Comments 0 Shares 2674 Views

- 1869 Sheriff Wild Bill Hickok breaks up fight, And kills a man.Just after midnight on September 27, 1869, Ellis County Sheriff Wild Bill Hickok and his deputy respond to a report that a local ruffian named Samuel Strawhun and several drunken buddies were tearing up John Bitter’s Beer Saloon in Hays City, Kansas. When Hickok arrived and ordered the men to stop, Strawhun turned to attack him, and Hickok shot him in the head....0 Comments 0 Shares 4749 Views

More Stories